The history of the world is inextricably linked to the history of trade, in particular, the widespread trade of goods obtained on the back of atrocities and those capable of shaping our entire monetary system. In Tracking the Trade Winds, we look at the seismic importance of gold, sugar, silk, oil and more in connecting civilisations, enriching empires and facilitating the migration of people and resources.

Unrefined petroleum has been used by humans for over 5,000 years, with the scientific community even arguing that the use of oil predates modern humans. From warfare to cooking to illumination, evidence of human consumption of oil extends into various sectors and periods. However, it was only in the 20th century that refined petroleum became a mass industry.

Oil catalysed the industrial revolution, fuelled global conflicts, and created entire economies from the desert. From the very beginning, oil has been a controversial resource and over the last few decades, has come under particular criticism for its role in the climate crisis. Big oil companies have faced the brunt of the blame, with The Guardian estimating that in 2020 top 20 oil producers were responsible for 35 per cent of all energy-related carbon emissions worldwide since 1965.

Compounding the blame, reports now indicate that oil executives knew about the environmental risks of drilling as early as 1955, but chose to conceal that information from the public. As people become more aware of the adverse impact of oil, calls have been made for a transition towards green energy. However, for a number of reasons, that transition has been a slow process. As the American activist Ralph Nader once said, “The use of solar energy has not yet been opened up because the oil industry doesn’t own the sun.”

The origins of refined petroleum

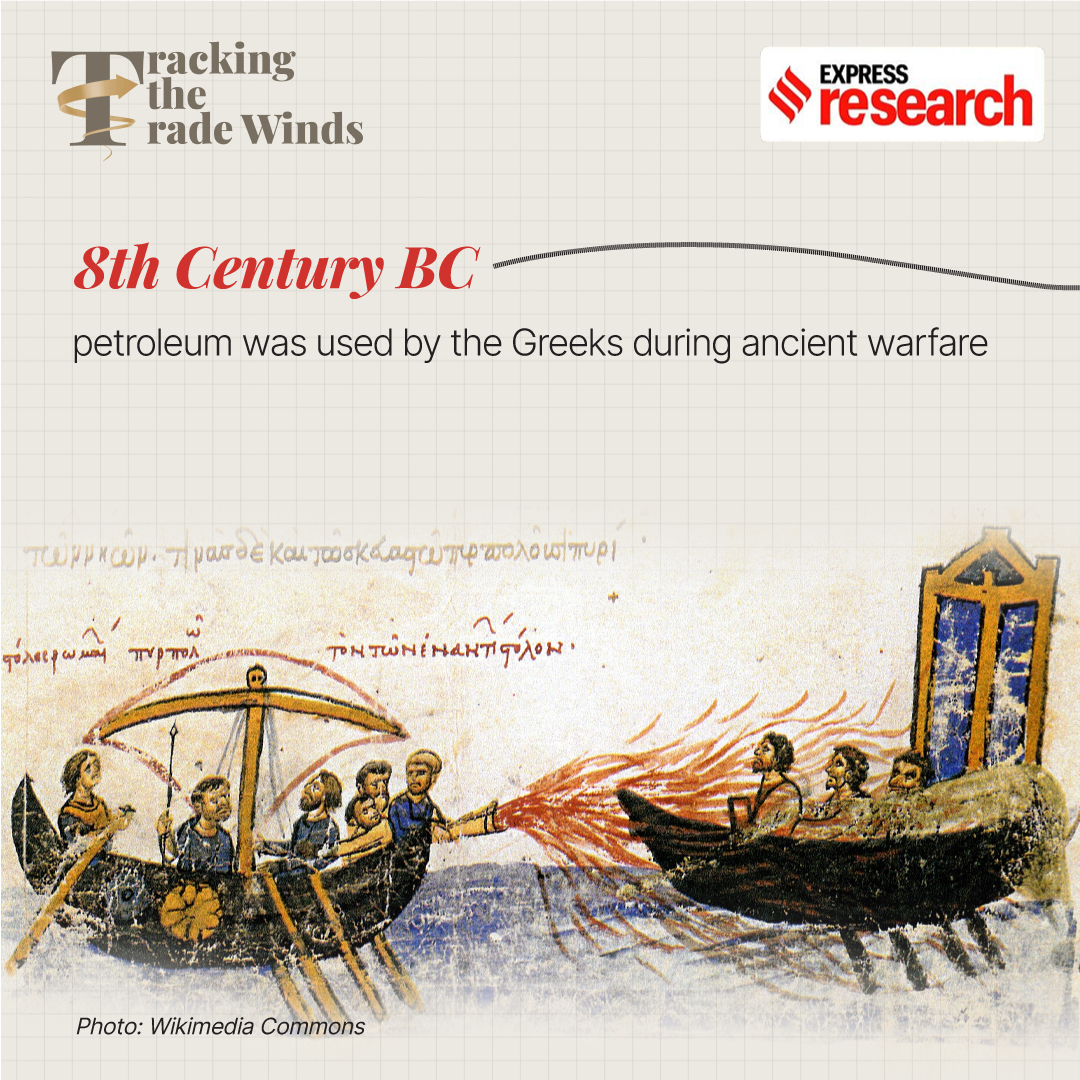

Oil in its unrefined form played an important role in ancient warfare with Homer writing in the Iliad that “the Trojans case upon the swift ship unwearied fire, and over her forthwith streamed a flame that might not be quenched.” In Bitumen and Petroleum in Antiquity, historian R J Forbes writes that oil was a decisive part of warfare from the seventh century onwards, with the Byzantines referring to it as Greek fire.

Arab and Persian chemists also distilled oil to produce flammable products and with the expansion of Islamic Spain, it reached Western Europe in the 12th century. This distilled oil was highly volatile, prone to causing fires, and difficult to control. By the 1600s, it was the primary source of lighting but was soon to be replaced by a cheaper, safer and far more accessible alternative.

The Persians used oil in warfare

The Persians used oil in warfare

Before refined petroleum, whale oil, derived from the blubber of right and sperm whales, was the accelerant responsible for illumination. Whaling was one of the first great multinational businesses and in 1852, when Moby-Dick was first published, was the employment of choice for ambitious young men. In 1853 alone, 8,000 whales were slaughtered off the coast of America, with their oil shipped around the world. However, as demand for blubber rose, whales became scarce, and hunting them became an ordeal of life and death. Oil refineries existed in parallel with the whaling industry but it was only after the sharp decline in whales that other alternatives were sought out.

Advertisement

In 1745, under Empress Elizabeth of Russia, the first oil well and refinery was built in Ukhta by Fiodor Priadunov, who, through the process of distilling rock oil, produced a kerosene-like substance that was used in oil lamps.

Before refined petroleum, whale oil was the primary source of illumination

Before refined petroleum, whale oil was the primary source of illumination

The production of paraffin from crude oil marked the beginning of petroleum’s modern history in the 19th century. James Young, a Scottish chemist, discovered a natural petroleum seepage at the Riddings colliery in Alfreton, Derbyshire, in 1847. He then distilled the natural petroleum to create a thin, light oil suited for use as lamp oil and a thicker oil ideal for lubricating machinery.

Less than a decade later, George Bissel, considered the Father of American Oil, discovered that he could use the same drills used to extract salt from the ground, to recover oil. And with that, writes Nobel laureate Daniel Yergin in The Prize, “Man was suddenly given the ability to push back the night.”

Advertisement

Bissel set up the first American oil company in Western Pennsylvania which was a rapid success. Oil production in the state went from 450,000 barrels in 1860 to three million barrels in 1862. In July 1865, a farm that had been practically worthless only a few months earlier was sold for $1.3 million, and then in September it was sold again for $2.3 million.

According to Yergin, “from the very beginning the race for oil involved extracting every last drop of it possible” due to the American doctrine of ‘rule of capture’. The rule of capture, as it was used in oil production, allowed different surface owners above a shared pool to take all the oil they wanted, even if doing so disproportionately depleted the pool or decreased the output of surrounding wells and neighbouring producers. Therefore, it was inevitable that the owners of nearby wells would engage in fierce competition to produce as much as they could and as quickly as possible to prevent another from draining the pool.

George Bissel was considered the father of American oil

George Bissel was considered the father of American oil

Even then, the adverse impacts of oil were well documented, with Yergin writing that “the rule of capture led to considerable waste and damage, to the detriment of ultimate production from a given pool.”

However, oil was the most sought-after commodity of the day, and despite its many risks, people rushed to capitalise on its immense potential. The most important of those people was John D Rockefeller, founder of the Standard Oil Company, aptly nicknamed the King of Oil. Rockefeller’s success stemmed from his decision to consolidate oil refining into one giant industry. With that step, by 1879, Standard Oil controlled 80 per cent of America’s refining capacity, almost all the pipelines and transportation linkages.

The spread of oil internationally

Initially, sailors were terrified to carry kerosene as cargo due to its heightened flammability. However, in 1861, the first cargo ship carrying petroleum made its way safely to London and with it ushered in the global trade of oil.

Advertisement

Russia soon emerged as the biggest market for American oil. With its capacity to provide light, oil revolutionised the Russian workday, which during winter months was restricted to six hours of daylight. By 1875, Russia was so dependent on American oil that its government abolished the Russian monopoly system and opened the oil market to private enterprise.

Russian oil production increased from less than 600,000 barrels in 1874 to 10.8 million barrels a decade later, or about a third of American production. By the early 1880s, about 200 refineries were operating in Baku’s (the capital of Azerbaijan) new industrial neighbourhood, which was appropriately called Black City.

Advertisement

Baku established the first major oil refinery in Europe

Baku established the first major oil refinery in Europe

The rapid expansion of Russian production, Standard Oil’s dominant position, and the competition for existing and emerging markets during a period of rising supply were all elements in what came to be known as the Oil Wars. Four rivals — Standard, the Rothschilds, the Nobels, and the other Russian producers — engaged in a protracted conflict for control over the resource in the 1890s.

As Yergin writes, “At one moment, they would be battling fiercely for markets, cutting prices, trying to undersell one another; at the next, they would be courting one another, trying to make an arrangement to apportion the world’s markets among themselves; at still the next, they would be exploring mergers and acquisitions. On many occasions, they would be doing all three at the same time, in an atmosphere of great suspicion and mistrust, no matter how great the cordiality at any given moment.”

Advertisement

The search for oil in the Middle East began in 1901 when a British businessman named William D’Arcy convinced the Persian government to award him a concession for oil exploration and extraction. D’Arcy, whose initial efforts were unsuccessful, appealed to the British government for help and in 1905, was given financial assistance by Burmah Oil, which was later renamed British Petroleum.

In 1909, when D’Arcy and Burmah first reorganised their oil holdings into a consolidated entity, shares for its initial public offering sold out within 30 minutes in London, kickstarting the race for oil in the Middle East. However, despite a stream of European powers competing for influence, oil production in the Middle East didn’t take off until the 1950s.

Oil transformed the Middle East

Oil transformed the Middle East

Even after the Second World War, Middle Eastern countries lacked the equipment and expertise necessary to extract oil. As a result, Western businesses were able to acquire oil exploration and extraction rights for a pittance. Over 60 per cent of the world’s supply would eventually come from production in the Middle East.

As the Middle East started to recognise its power in the 1950s, the balance of power changed. During the Suez Crisis, Britain saw first-hand the impact of this change as Middle Eastern oil imports into Britain via the Suez Canal ceased. The influence of other oil-producing countries started to spread around this time.

Following American backing for Israel during the Yom Kippur War against Egypt and Syria, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) called for an oil embargo against the West in 1973. Oil prices nearly doubled as supplies became scarce. Over time, the discovery of oil in the North Sea and the developing of hydraulic fracking in North America gave both the UK and the US some respite from the clutches of OPEC but as the conflict in Russia demonstrates, the demand for oil continues to shape geopolitics.

Migration to the Gulf

The surge in oil prices during the middle of the 20th century led to the creation of “rentier states” in the Persian Gulf. Due to their small populations and abundance of oil, rental revenues from natural resources dominate government revenue thus eliminating the need to impose high taxes on the local population. Onn Winckler of the University of Haifa, in his article Labour Migration to the GCC States, explains that because so many Gulf countries had oil revenues exceeding 80 per cent of governmental income, their governments were able to redistribute the money by increasing public sector employment and salaries.

The end result, he writes, “Was the creation of a dual labour market with nationals employed almost exclusively in the public sector while the vast majority of the foreign workers were employed in the private sector.”

This migration of non-Arab foreign workers to the Gulf states, predominantly from India and the Philippines, occurred in three main waves during the 1970s and the 1980s, largely as a result of the oil price boom in 1973. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), India is one of the two top origin countries (apart from the Philippines) of migrants to the Gulf.

John D Rockefeller was the first man to accumulate billions from the sale of oil

John D Rockefeller was the first man to accumulate billions from the sale of oil

Indian migration to the Gulf fluctuates with the ebbs and flows of oil prices. When prices are high, as they were in the 1980s, the demand for low-skilled labour increases. However, as the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) has reported, when prices fall, as they did in the 2010s, Gulf countries tend to enact measures that prioritise local workers at the expense of foreign nationals. According to the ORF report, Indian emigration to the Gulf halved between 2015 and 2017 when oil prices were low, but then increased by 20 per cent between 2018 and 2019, as oil prices started to rise and Indian companies won large contracts in the region.

While migration to the Gulf has had many benefits in terms of remittances and addressing domestic workplace shortages, the kafala, or sponsorship, system under which migrants are recruited and hired faces significant allegations of exploitation. These problems range from exorbitant visa fees, confiscation of passports, poor working conditions, unsanitary living conditions, and difficulties obtaining exit visas.

In addition to attracting migrants, oil reserves in the Gulf, and the politics born from them, have a significant impact on global energy security. The Gulf states, and by extension, OPEC, have used this leverage to devastating consequences in the past, triggering economic crises in 1973 with the Arab oil embargo and in 2022 with the OPEC+ decision to cut oil production. In 1973, the struggle between OPEC and the US was so disruptive to the American economy that economist Ed Morse wrote in Foreign Policy magazine that OPEC had brought “the West to its knees.” Former US presidents including Gerald Ford and Donald Trump have referred to the organisation as a cartel, calling on the US to pursue energy independence to escape the clutches of the Middle East.

As of 2022, OPEC controls nearly 40 per cent of the world’s oil supply, giving it an outsized influence over global politics. In a report for The Washington Post, Brown University’s Jeff D Colgan explains, “OPEC perpetuates the myth that it regularly manages the world oil market. That reputation means its members receive more diplomatic attention than they otherwise would.”

Oil has been a boon for the Middle East, helping them to build modern cities and provide their residents with a much higher quality of life than in other Asian countries. However, Gulf countries are cognizant of the fact that oil doesn’t last forever. Bahrain and Oman are acutely affected by this reality as their reserves are expected to run out within 10 and 25 years, respectively. To address the problem, Gulf countries have embarked on a strategy of diversification with the UAE arguably being the most successful and Saudi Arabia, the most ambitious. Despite these efforts, as the Brooking Institution reported in 2021, the Gulf is still heavily dependent on hydrocarbons, their economic success contingent on the supply and demand of oil.

The environmental cost

Despite the push to shift towards green energy, the position of oil has remained dominant. Put simply, oil is used in almost every facet of modern life. It’s used to generate electricity, to power cars, trains, ships, and planes, it’s used in manufacturing, in agriculture, in technology, in textiles, in pharmaceuticals and almost every other industry one can think of.

While oil companies are now facing the heat, reports suggest they knew about the adverse effects of oil for many decades. In fact, environmentalist Bill McKibben once characterised the fossil fuel industry’s campaign to conceal the information as “the most consequential cover-up in US history.” As early as 1950, scientists who worked for the fossil fuel sector were aware that CO2 emissions could have a warming effect. ExxonMobil, American multinational oil and gas corporation, even had internal documents leaked that demonstrate that their scientists were explicitly aware of the potential risks posed by human-caused climate change caused by their products, but rather than acting or alerting the public, they instead invested millions of dollars in deception campaigns intended to obscure the scientific reality.

American Misled, a report produced by climate scientist John Cook of George Mason University, estimates that by the 1980s, a scientific consensus emerged that oil played a significant factor in human-led climate change. It asserts that “over the past few decades, the fossil fuel industry has subjected the American public to a well-funded, well-orchestrated disinformation campaign about the reality and severity of human-caused climate change.”

Against this backdrop, oil companies have been forced to change course. According to one study by Harvard University, the energy sector was the second highest producer of green patents, behind only the manufacturing industry. Companies like British Petroleum have long attempted to change their public image, even going as far as to rebrand the company to ‘Beyond Petroleum’. Investors in US-based oil company Chevron voted to cut emissions from the petroleum products it sells. Against massive public outcry, developers of the Keystone XL pipeline cancelled the project after decades of environmental concerns over the project.

Most Read

However, a recent report from the climate collaborative project Net Zero Tracker, says that while many fossil fuel companies are adopting the narrative of reducing emissions, most aren’t actively tackling the issue, making their promises “largely meaningless.”

According to American Representative Ro Khanna of the House Oversight Committee, oil companies are talking the talk without walking the walk. He remarked to the House Congressional Committee in 2021, “They’re basically saying, we’re going to increase production, we’re going to increase emissions, but we’re also going to be able to claim being this clean tech company, this green company, because we can take some symbolic actions that make it look like we’re in the climate fight.”

Oil companies have disproportionately controlled much of the world’s industry for the last two centuries. However, as the pressure to go green builds, they are increasingly being forced to change their ways. Whether they do so, or just profess to, is yet to be seen.

"Oil" - Google News

September 01, 2023 at 01:37PM

https://ift.tt/BKm6UoX

The dark story of oil, the lubricant of the global economy - The Indian Express

"Oil" - Google News

https://ift.tt/bquMFOk

https://ift.tt/1QmAozC

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The dark story of oil, the lubricant of the global economy - The Indian Express"

Post a Comment