Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column by Eduardo Prud’homme as part of a regular series on understanding this process.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas). Based in Mexico City, he is the head of Mexico energy consultancy Gadex.

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

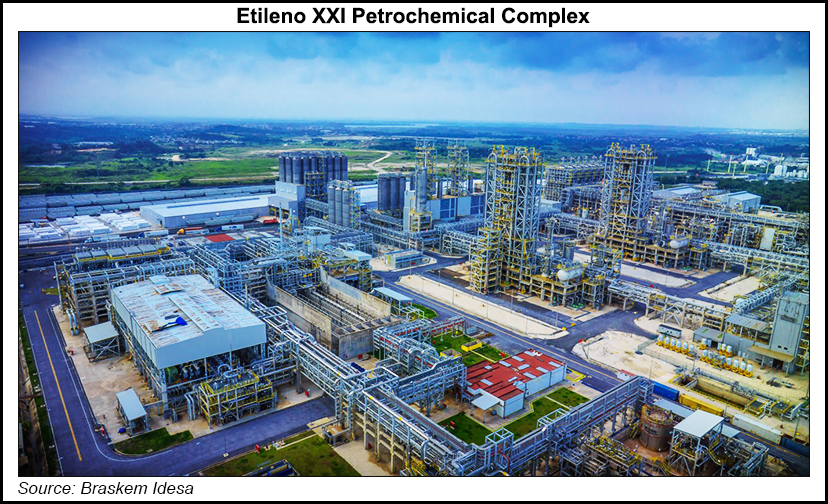

The decision by national pipeline manager Cenagas to suspend natural gas supply to the Etileno XXI petrochemical complex in Veracruz state has numerous implications for the energy sector in Mexico, principal among them the reputation of the country’s respect for contracts. But first, a little background.

In 2010, a consortium formed by Braskem and the Idesa group signed a 20-year, 66,000 b/d ethane supply contract with Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex). The ethane was awarded in an auction process and was destined for Etileno XXI. The ethane would come from the Ciudad Pemex, Nuevo Pemex, and Cactus processing plants, as well as the Cangrejera petrochemical complex. The streams would be transported through an ethane pipeline to be developed by Gasoductos del Sureste, then a subsidiary of Pemex and which today belongs to IEnova.

The price formula was regulated by Comision Reguladora de Energia (CRE). Before this project, Pemex did not sell ethane to third parties, and its ethane went to its petrochemical plants in the Coatzacoalcos area. Surpluses were mixed with natural gas flows in pipelines in the area. The supply contract model between Pemex and Braskem-Idesa reflected common negotiation practices in the industry. Among the contractual terms is the obligation to deliver ethane at a temperature between 18º and 28º Celsius. For this, the project needed a supply of natural gas as fuel to keep ethane within this temperature range, and as an input and fuel for the other cracking processes.

This gas supply would come from the Sistrangas national pipeline system run by Cenagas. In the 2017 open season, Cenagas granted the plant a transport contract on a firm basis for a maximum daily quantity of approximately 60 MMcf/d. This, despite the fact that gas availability in the area did not look very promising. In the last five years alone, Pemex gas production in the southeast has fallen by a third, and the gas it extracts is often high in nitrogen and used for its own purposes.

According to the Cenagas electronic bulletin board, gas consumption by Etileno XXI averaged 46 MMcf/d in 2017-2020. On rare occasions the flow exceeded the agreed upon amount, and given the increasingly acute gas shortage in the southeast, interruptible routes with injection points in Nuevo Pemex, KM Border, Tennessee, Nejo, Maregrafo, Ramones, Energy Transfer and Montegrande were used.

In early December, Braskem said it received notification from Cenagas “related to the unilateral termination of the service of natural gas transportation, an essential energy input for the production of polyethylene” at the complex.

“As a result, in compliance with safety protocols, Braskem Idesa initiated procedures for the immediate interruption of its operating activities, which may have a material effect on the company’s operating or financial results, depending on the timing of the stoppage,” the company said.

Clearly, this raises questions about the technical and operational independence of Cenagas as a guarantor of open access obliged not to discriminate against its users. Cenagas said it would not renew the firm transportation services contract for the transportation of natural gas and the next day it blocked the extraction of gas from the system, despite the fact that the interruptible contracts were still in force. During his morning press conference Wednesday, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said he’d been informed of the termination by Cenagas of natural gas transport service for the complex, which he said occurred “because the unfair [ethane] contract is not being corrected…” He added, “Therefore, there is no longer natural gas for the company because the [natural gas] contract expired. It wasn’t interrupted, but rather it reached its end date and will not be renewed.”

Although initially meant to only be one-year contracts, in 2018 Cenagas’ prevailing vision was to offer long-term contracts with no term limits. There was also no obstacle to the renewal process as long as the user or shipper complied with their payment obligations and has followed the rules set out in the Terms and Conditions for the Provision of Services (TCPS) for the management of transport capacity. The idea was to give long term certainty to the parties involved – certainty in obtaining the service for users, and certainty in the cash flow and collection of fees for Cenagas.

The Braskem-Idesa issue is a case where normal procedures were not followed. The contract renewal, which generally takes place in July, was decided on in November. It is strange that the end of the firm-based contract referred to did not end in June, 2021. Regarding cutting off supply when interruptible contracts are still effective, the possible valid justifications can only come from a lack of payment or a systematic breach of compensation for imbalances. Given the stable pattern of consumption at the extraction point E185, and that these are usually lower than the agreed upon amount, it would be difficult to think that there is an accumulation of imbalances. In any case, there are terms and provisions in the TCPS that give users the opportunity to have continuity in services and protect the operator’s finances with the execution of the payment guarantees that accompany the signing of the contracts. That the compensation mechanisms characteristic of interruptible contracts ended at the same time as the validity of the firm contract would be a remarkable coincidence.

The reasons for the suspension of the service have little to do with the operation of Sistrangas and with the commercial structure of the contracts in the area. The government played hardball in a similar way last year with natural gas pipeline contracts with private sector companies. President Lopez Obrador doesn’t like the ethane contract in place and he points out that it was signed during the Felipe Calderón government, his most conspicuous rival. Moreover, the consortium has ties to a company accused of corruption and involving Peña Nieto: Odebrecht.

Behind this discourse there are several facts that suggest strategic behavior. For starters, natural gas supply is precarious in the southeast. The volume injected into the Sistrangas hardly reaches Coatzacoalcos. Etileno XXI is the largest private natural gas user in tariff zone 8. The largest extraction in the zone is in Cuanduacán, where natural gas is used to keep crude oil production afloat. If the downward trend in production continues, sooner or later the dilemma would be: deliver gas to Pemex’s upstream arm (PEP), or Etileno XXI. Not renewing a contract solves a situation without Cenagas or Pemex having to pay penalties for leaving a user stranded.

But the Cempoala compression station will help get more gas to the southeast, and should be seen as a solution to the issue. However, such a solution obstructs a potential preferential allocation of capacity for CFE from Montegrande to Cuxtal. Pemex is now free of responsibilities for its supply obligations because it is materially impossible for Pemex to deliver gas in the vicinity of the plant without capacity on a pipeline.

The second consequence of the disruption is even more relevant. Having no gas supply, Etileno XXI must cease operations. When operations stop, it will stop taking the ethane that Pemex delivers via the ethane pipeline. The imbalance clauses have certain flexibility, however whatever the shortfall in consumption in one quarter, Braskem-Idesa would have to make up for in surplus consumption in the following two quarters. If it does not do so, it will have to pay Pemex damages that may amount to $200 million dollars. Paradoxically, it is possible to imagine a scenario in which Pemex is the one aggrieved by the interruption of its supply service in collusion with the system operator – even though Pemex was on track to be the one not able to meet the commitment due to falling production.

Default delivery clauses also give the seller some flexibility. But they force subsequent ethane deliveries in compensation that Pemex could hardly meet given current production conditions. After two quarters without restoring the average in the committed amount, Pemex would have to pay damages that could rise up to $300 million, or the government would even be obliged to buy the plant.

The affair makes explicit the inexistence of independence between Cenagas and Pemex. It’s another example of mixed messaging from this government. Two days earlier, an infrastructure plan was announced that includes a pipeline on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and IEnova’s liquefaction plant in Ensenada to go with the one CFE plans to build in Salina Cruz. The conclusion is that in this administration, energy investment will occur only with the explicit invitation of the government and that contracts will be subject to the government’s interpretation of them.

"gas" - Google News

December 05, 2020 at 05:05AM

https://ift.tt/2Ic3jEm

COLUMN: Cessation of Gas Supply to Etileno XXI Worrying Sign for Energy Industry - Natural Gas Intelligence

"gas" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2LxAFvS

https://ift.tt/3fcD5NP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "COLUMN: Cessation of Gas Supply to Etileno XXI Worrying Sign for Energy Industry - Natural Gas Intelligence"

Post a Comment